Women were overlooked in the early years of AIDS

This article was produced in honor of San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s 40th anniversary, which we are commemorating in 2022.

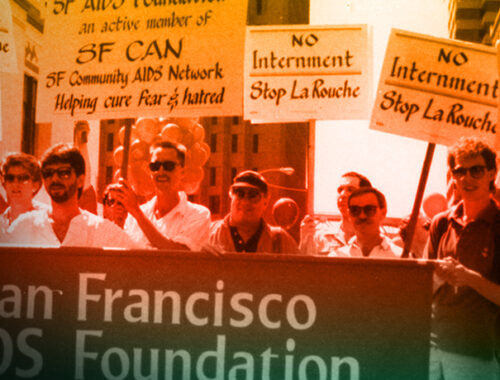

The earliest incidents of what was to become known as AIDS appeared in gay men in Los Angeles and New York City. For a long while, it seemed that the disease afflicted only gay men—hence the early names like “gay cancer” and “GRID” (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency). The perception that AIDS was exclusively a “gay disease” persisted for several years, not only in the public eye but also in the medical community. Thus, women in the HIV community have been overlooked and mistreated since the beginning of the pandemic.

Example: It took several years for the CDC to revise its definition of AIDS to include women, even though women had indeed been contracting and dying from AIDS. Before the definition change, women were routinely blocked from clinical trials of HIV medication because “women don’t get AIDS.”

As Sarah Schulman points out in Let the Record Show, another reason for the exclusion of women in clinical trials was over fear of possible medication exposure to unborn babies. In the 1960s, there was a disaster with thalidomide, a medication for morning sickness, that caused thousands of children to be born without limbs. Fearing liability if something similar happened with the new HIV drugs, pharmaceutical companies limited their trials to men only instead of requiring participants to be on contraceptives or otherwise ensuring that pregnant women weren’t included in trials. But as Schulman also points out, the primary reason for the exclusion was simple neglect. “[A]t the time, science did not think about women.”

As the number of women living with HIV grew, the country’s AIDS service organizations (ASOs) were ill-equipped to counsel and serve HIV-positive women. Some simply didn’t try. In conversation with three women who are long-term HIV/AIDS survivors with ties to the San Francisco Bay Area, I learned that even services in San Francisco at times did not, or could not, meet the needs of HIV-positive women.

“I tested HIV positive in June 1990,” Rebecca Dennison told me. She was 28 years old. “I went [to the testing site] to support a friend who was nervous about getting tested. I assumed that since I’d been in a monogamous relationship with my husband for 5 years that I wasn’t at risk. I was very wrong about that.”

Rebecca looked for a place to meet and talk with other women living with HIV, but wasn’t able to find what she was looking for in San Francisco or in the East Bay. She found support groups for women living with HIV, “but I didn’t qualify for them. There was a group for lesbians. A group for African American women. A group for women in recovery. A group for Kaiser patients. There were also places that advertised that they had groups for women but when I tried to enroll, they put me on a waiting list that led to nothing.”

Summarizing her early experience, Rebecca said, “Every human needs to feel safe and loved. We all need to belong somewhere.”

Award-winning author and long-term survivor Martina Clark was also diagnosed with HIV in the early 1990s. “I’d just moved to Novato to live with my sister and her family so I could save money with the intent to move overseas. It was a shitty April 29th [1992]. I’d been feeling lousy for months so in early May, I went to my sister’s family doctor. Ten or so days later the doctor called, while I was housesitting in San Francisco, with the results that I was HIV-positive.”

She went to the Marin AIDS Project (MAP) in San Rafael and formed a close relationship with her case worker Penny Chernow. “There was no sugarcoating, lots of kindness, but no bullshitting for which I was extremely grateful. I stayed in Marin for another year and change; I moved back to San Francisco in fall of 1993.”

Martina said, “I never contacted SFAF for assistance. The truth is, I never saw SFAF as a place for services for me. I viewed SFAF as a big beast that raised money for the cause, advocated for rights and needs of people living with HIV, and helped to set policy. To be clear, I saw their work as invaluable and that without it, this country would not have had a viable response to the pandemic. But I definitely saw them more as a policy and advocacy organization than a hands-on AIDS service organization.

“I did attend a SFAF training for their hotline,” Martina continued, “although in the end I never volunteered because, again, I felt like I wasn’t sure I’d be able to answer the needs of the population I felt SFAF was serving. Even then, as an HIV-positive woman, entrenched in the positive-community, I didn’t see myself as a part of their clientele. I valued and respected their work, still do, but I never felt included. I will say, however, that the training was great and served me well in the years that followed, and I am forever grateful to have had that opportunity.

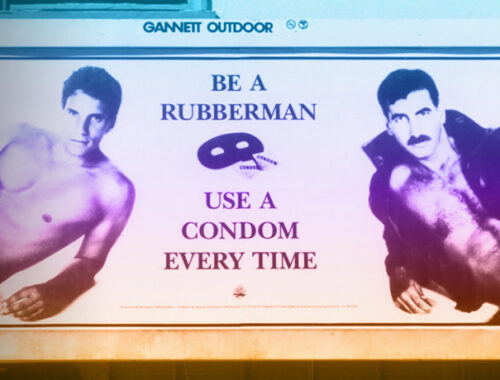

“Finding services for women was a sort of underground, word-of-mouth affair rather than the in-your-face campaigns for men,” Martina continued. “I don’t begrudge the campaigns for men. They were necessary. But our absence was more than an oversight, it was a public health fuck-up that went far beyond San Francisco.”

Both women continued their search for other women living with HIV and for services available to them. For Rebecca, “The first woman I met was the sister of the friend I accompanied to testing. She had advanced AIDS, was taking AZT every 4 hours at doses we now know were way too high. Seeing her, lying in bed, struggling to keep her head up, in so much pain, I saw two things: A friend/mentor I desperately needed, and my future.”

While participating in an AIDS Walk at Stanford, she met another HIV-positive woman who was involved in ARIS Project in San Jose. “They had mixed groups that were for anyone with HIV (any gender, any sexual orientation). I met a couple women in San Jose through her, but that was a long drive.” As a member of ACT UP Golden Gate, she attended the first National Conference on Women and AIDS in Washington, DC. “At that conference, and even on the plane, I finally started meeting other HIV-positive women who lived near me. A lot of them became early participants and board members of WORLD (Women Organized to Respond to Life-threatening Diseases).”

Rebecca had thought for some time about starting a newsletter by and for HIV-positive women. “When the first woman I had met died, her mother asked me to speak at her memorial. In that speech, I pledged to start a newsletter for HIV-positive women. People immediately started giving me names and addresses for the mailing list, and encouraging me to follow through.” Thus, WORLD was born and became a tremendous resource for women living with HIV, a platform for women living with HIV to speak and advocate for themselves. Martina Clark was one of those women.

“I met Rebecca Denison and the community of women she’d been welcoming into WORLD, her organization to support women living with HIV. That is where I really connected with other positive women and began to make connections on a deeper level, many that last to this day. Many more that would also have lasted if people didn’t keep dying, damnit,” said Clark.

Ms. Hulda Brown, a long-term HIV survivor, also met other HIV-positive women through WORLD. In March of 1991, Hulda and her boyfriend were collecting cans and plastic bottles to recycle for extra cash. “Someone had put a plastic grocery bag in the bin with needles in it,” she told me. “I was wearing my boyfriend’s gloves with the ‘bird’ finger cut out. I got stuck in that finger.” She waited three months to seek help.

“Both of my sons were in the Gulf war at that time. I didn’t care about myself at all at the time. All I wanted was for my sons to come back home safe. When I could no longer bend my finger, and my lymph nodes were swelling all around my neck, I went to the doctor to see what was wrong. I knew nothing at all about HIV. At that time I was very much of an introvert. I was afraid to talk to people, and I was afraid to have people talk to me.” The clinic she used referred her to San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

“At that time HIV was considered to be a gay white male illness. I am a straight Black female. There was very little information about women at that time. There was one counseling group [at SFAF]. That was when I discovered that women could get this illness too. I felt I was being tolerated in this basically male world. At times I was told, ‘This is a man’s group, but you are welcome to sit in.’ I usually just sat to the side and listened.”

Through SFAF, Hulda learned about WORLD and began educating herself about HIV/AIDS. “First I had to gather the courage to ask questions. Then I had to figure out which ones to ask without seeming like a total idiot. I got blown off, ignored, and chastised. I got treated like a child. I got told, ‘Don’t you ever tell anyone how you got it because no one will ever believe you.’ I learned how to ask questions, and NOT ask questions. I learned that if you listen a little you learn a lot. I am still learning. There are still a lot of questions about women and HIV that I would like the answers to.”

Summing up, Hulda said, “I can say that SFAF was a very good start because it gave me the answers I was seeking at that time, but we still have a long way to go.”

A long way to go, indeed. I asked all three women, “What do you think ASOs could do to improve the way they treat women living with HIV?” Their responses were detailed and full of common sense. “Ask women what they want,” Martina said. “Hold focus groups and ask them what they want. Make the services women-centered. End of story. It is not that hard. There are examples to refer to, but most importantly, ask women what they want, give them a seat at the table to feed into the decision-making processes. Ask them!”

Commemorating 40 years

Join us every month in 2022 as San Francisco AIDS Foundation marks 40 years of service to the community.

On this occasion, we take a look back and share our storied history of leadership in HIV prevention, education, advocacy, and care, and HIV history in San Francisco and the Bay Area since the beginning of the epidemic.

As we look back on our history, we approach the future with hope, and with a renewed sense of all that our passion and ingenuity can bring to enact positive change in our community. We will act in bold and brave ways to reach an end to the AIDS epidemic, and ensure that health justice is achieved for all of us living with or at risk for HIV.

After 40 years, we will not lose sight of our commitment to our community, and our vision for a brighter future.