Timothy Ray Brown, first person cured of HIV, “never wanted to be the only one”

I get peace of mind knowing I’ve done what I can to help bring about a cure for HIV. — Timothy Ray Brown

At the XVII International AIDS Conference in Mexico City in 2008, researchers stunned the gathered conferees, and indeed the entire medical world, when they announced that a physician in Berlin, Germany had “cured” a man of HIV—or more accurately, that Dr. Gero Hütter, a hematologist, had successfully eliminated the virus from the patient’s body.

The patient, a gay man living and working as a translator in Berlin, had been diagnosed with HIV in 1995 and then, ten years later, at age 40, was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a cancer that causes bone marrow to make abnormal cells. In 2006, the “Berlin Patient,” as he became known, underwent a bone marrow transplant with stem cells collected from a donor with a particular CCR5-delta32 mutation that protects T-cells from getting infected with certain strains of HIV, and a second transplant in 2007 when his AML returned. After the second transplant, his AML went into remission. Dr. Hütter examined the patient for traces of HIV in his body but could find none. Dr. Hütter and his team were very careful not to use the term “cured,” when referring to their patient; they called it “long-term remission” instead.

Still, the welcome headlines—“Berlin Patient Cured of HIV”—quickly spread throughout the world, engendering hope that the virus could finally be eradicated. That hope dimmed when researchers explained that the bone marrow stem cell transplant procedure was far too risky, too expensive, and not readily available enough to be considered a viable cure for the millions of people living with HIV. Those hopes dimmed to a faint flicker when Dr. Hütter tried, and failed, to replicate the Berlin Patient’s success story with other patients.

Doctors in the U.S. have tried similar potential HIV cures, also to no avail. Researchers concluded that the procedure should not be performed on others with HIV, even if sufficient numbers of suitable donors could be found. Since then, most “cure” attention has been focused on preventative and therapeutic vaccine research. Thus far, the Berlin Patient remains the only person to have HIV eliminated from his body.

For the sake of privacy, doctors referred to the “Berlin Patient” anonymously for years. Until 2010.

“I was not ready for publicity but, at the end of 2010, I decided that I would release my name and image to the media. I went from being the ‘Berlin Patient’ to using my real name, Timothy Ray Brown. I did not want to be the only person in the world cured of HIV; I wanted other HIV+ patients to join my club. I want to dedicate my life to supporting research to search for a cure or cures for HIV!” [1]

With that brave act of disclosure, Timothy Ray Brown instantly became an icon in the LGBTQ+ and HIV communities around the world and kickstarted his fierce, passionate advocacy for research into a more accessible cure for HIV/AIDS. “I wanted to do what I could to make [a cure] possible. My first step was releasing my name and image to the public.” He traveled across the globe, talking at schools, activist gatherings, and national and international AIDS conferences.

His partner of eight years, Tim Hoeffgen, told the Bay Area Reporter, “Tim really inspired a lot of scientists to continue doing cure research and he really loved interacting with medical students, scientists, HIV activists; he really wanted everyone to have a cure for HIV on a mass scale.” Together, Hoeffgen and Brown continued their activism until a recurrence of acute myeloid leukemia took Timothy’s life on September 29, 2020.

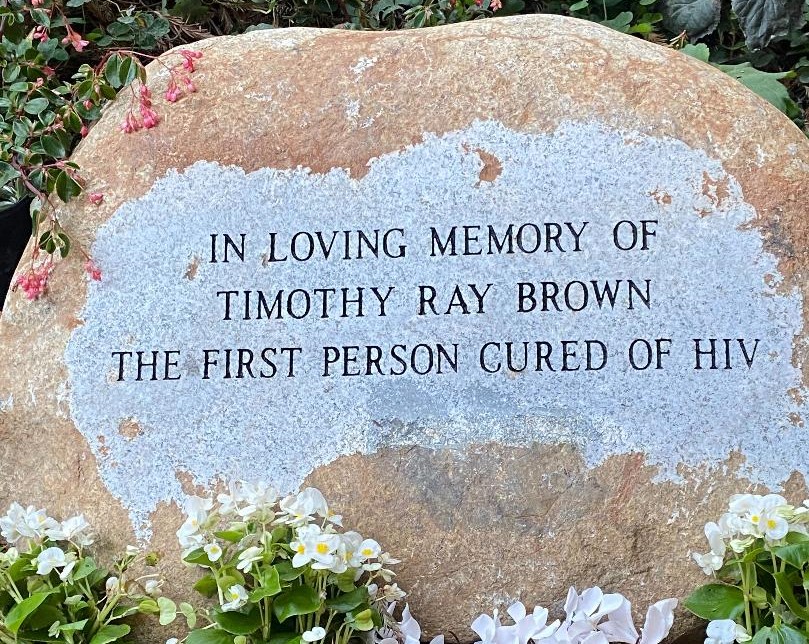

To commemorate Timothy’s life and his impact on the HIV/AIDS community, a consortium of friends and organizations (including Let’s Kick A.S.S. (AIDS Survivors Syndrome) Palm Springs, amfAR, Desert Healthcare District & Foundation, HIV+AIDS Research Project-Palm Springs, and the Until There’s a Cure Foundation) collected funds to memorialize Timothy with an engraved boulder in the National AIDS Memorial Grove in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. The boulder was installed at a ceremony in the Grove on October 16, 2021. The inscription on the boulder reads, “In loving memory of Timothy Ray Brown, the first person cured of HIV.”

Speaking of the last year of Timothy’s life, Hoeffgen said at the ceremony, “It was really a difficult time, but I’m thankful that all this came to fruition. I thank all the donors and volunteers that are here today. I’m glad that everyone’s out here today. Thank you very much.” I was curious what was going through Tim’s mind as he listened to others memorialize Timothy. “I was thinking how beautiful the location of the boulder is and feeling at peace the day of the dedication.”

Among those in attendance were SFAF’s Director of Aging Services Vince Crisostomo; Gregg Cassin, Director of Honoring Our Experience; AIDS Grove CEO John Cunningham; Paul Aguilar, Chair of the HIV Caucus at the Harvey Milk LGBTQ+ Democratic Club; and other local activists, including Joanie Juster, Ed Wolf, Matt Sharp, and some forty others.

I had the chance to chat with a close friend of Timothy’s, Butch McKay, Director of the Positive Living Programs for OASIS Florida and founder of the 23-year-old Positive Living Conference, who attended the ceremony in October. Butch first met Timothy at the 2012 International AIDS Conference. He invited Timothy to deliver the Keynote address at Positive Living 16 in 2013, an invitation Timothy gladly accepted. Butch spoke very warmly about his friendship with Timothy. “Timothy loved not only meeting new people but getting them to share their stories. He never tired of listening to the stories and was always supportive of people sharing. We ran into each other at other events and kept connected via email and phone calls. He never wanted to be the only one cured. He wanted everyone cured. He said, this is the beginning.”

Turning to the initial impact of the news that a patient had been cured of HIV, I asked Butch how he first reacted when he first heard the news. “I welcomed the news. Having been part of three research networks starting back in the 1980s, I believed this was news that would create hope. To be honest, I was also skeptical since the person was not identified. That bothered me a lot.”

Although many of us living with HIV (including me) experienced quite a letdown when we learned that the procedure was too risky, too expensive, and too uncertain to be used universally to cure HIV, Butch never let his hope dim. “I knew that this would not be the end all and that it wouldn’t be for everyone,” he told me. “However, there was no denying it cured him, and that was exciting and crested an atmosphere of hope that research could soon find other options that would be successful for the general HIV+ population.”

Paul Aguilar also told me of his reaction to hearing about the Berlin Patient. “I was dubious to say the least. So many false claims had been made over the years, I figured this, too, would be just another National Enquirer story right up there with ‘My Wife Had My Brother’s 200-lb Baby.’ Then, when I read a little more I was encouraged that it was an actual thing. Someone had been cured! But later, when I read further into the details as to HOW it happened, I felt that once again we were victims of the old ‘bait and switch.’”

With the commemorative boulder in the AIDS Grove—as well as a memorial bench and plaque in the Wellness Park adjacent to the Desert Regional Medical Center in Palm Springs, where Hoeffgen and he lived at the time of his passing—the HIV/AIDS community has honored a genuinely selfless, passionate advocate and internationally recognized hero. “I think Timothy’s legacy will be that he inspired HIV researchers with their work to find a cure for HIV and he gave hope to those of us living with HIV,” Hoeffgen told me. “Timothy would think that his legacy would be that his cure showed that a cure for HIV for all is possible in the not-too-distant future.” His legacy of hope in the face of great suffering will continue to inspire advocates and activists in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

Again, Butch McKay:

“Timothy’s legacy will always be that he was first to be cured of HIV, but there was so much more to him than just being cured. He never stopped fighting for others. He allowed his body to be used and sometimes abused by researchers studying his case, constantly asking him to go under countless medical procedures in hope to learn more. He never wanted to be in the spotlight but accepted that as his role to help others. He never used his fame for personal glory, but instead to spread hope I will remember him as a kind, loving, gentle soul who deeply enjoyed people. He was my friend.

“I like to think when he was born the world felt the warmth of a sunrise filled with hopes and dreams, and when he passed he left us with the beauty of the sunset filled with a sense of accomplishment.”

[1] Timothy Ray Brown (January 12, 2015). “I am the Berlin patient: a personal reflection.” AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses