Standing on the sidelines was no longer an option

This article was produced in honor of San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s 40th anniversary, which we commemorated in 2022.

Watching news reports of American and European ex-soldiers and others volunteering to travel to Ukraine and take up arms against the Russian invaders who are razing the country and slaughtering innocents, my heart fills will respect and admiration for those volunteers. It takes a special kind of person, a special kind of altruism, compassion, and care, to be willing to upend one’s own life and volunteer to “fight the good fight” no matter the odds, no matter the size of the enemy.

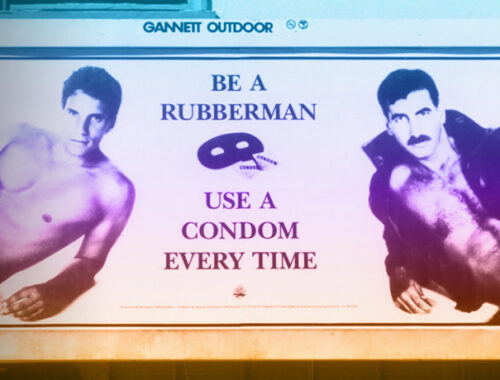

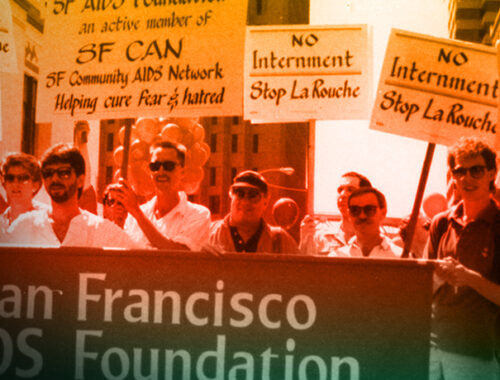

Those brave, selfless volunteers going to fight in Ukraine also reminded me of the legions of volunteers who rushed to the frontlines of the fight against AIDS in the 1980s and ‘90s. At a time when those of us who are HIV-positive were literally fighting for our lives, thousands of volunteers jumped into the fray — helping to raise funds for research, comforting and aiding those afflicted with AIDS, engaging in civil disobedience when necessary, setting up cannabis dispensaries (illegal at the time) and “buyers’ clubs” for experimental treatments, establishing direct-action service organizations like SFAF, Shanti, Project Open Hand, and others. Doctors, lawyers, nurses, artists, musicians, drag artists, organizers, fundraisers, civic leaders, clergymen, and other ordinary folks did extraordinary volunteer work alongside us.

As San Francisco AIDS Foundation commemorates its fortieth year of service, we caught up with four of those ordinary people who did, and continue to do, much-needed, substantive work in the HIV/AIDS community. Ed Wolf, Cal Callahan, Harry Breaux, and Joanie Juster are all well known and loved in this community for their innumerable hours of volunteer work, their compassion, and their undying dedication to the fight against AIDS.

Ed Wolf has been a towering figure in San Francisco’s HIV community since the very beginning. He first volunteered with Shanti in 1983; he served as a Shanti counselor on the AIDS Unit (Ward 5B at San Francisco General Hospital) from 1986 to 1989, then an Emotional Support Volunteer Coordinator, and then Lead Trainer until 1991. He facilitated trainings for SFAF’s hotline volunteers and often referred people to the Foundation for information and guidance.

“Back then,” he told me, “especially before the treatment success of the 1990s, being involved with the AIDS epidemic felt like a calling, like joining the military to fight a war. Some people heard the call and became lifelong veterans, like me. Others did their volunteer time and then went back to school to become therapists, doctors and so forth. This would be a fascinating story down the road… what happened to the early volunteers who survived.”

Harry Breaux is one of those early volunteers who survived — and thrived. As it was for many volunteers, Harry’s volunteer work was prompted by personal grief. “One afternoon in 1984, I listened to a voicemail that told me my friend, Victor LeNoble had died at General Hospital of some strange pneumonia. Knowing that the “gay cancer” was alive and rampant, I knew I had to do something to help. I signed up for the volunteer training at Shanti and completed the Emotional Support Volunteer program led by Jim Geary. Soon I was assigned a client named Eddie who was grieving the loss of his partner. I was also assigned a client, Andrew, a San Francisco Opera conductor who was diagnosed with AIDS and was slowly dying from the complications. I met with each of them weekly or more frequently when needed. Andrew would have some hard times and then would recover and didn’t need so much attention. Being an ear of support was my main objective and quite often I would also join them for lunches or events. Being a dependable and confidential “friend” was the most important aspect of the volunteerism for both types of situations.

“It was also during one three-month period while serving these men, that my own roommate became quickly terminal with AIDS and for a two- or three-week period, I took care of him as his sole caretaker until he passed away.” Like many people who threw themselves completely into volunteer work for the community, Harry found all the grief somewhat overwhelming. “About that time, I was having difficulty continuing and gave up being an active volunteer and focused on my own immediate needs as the grief was taking its toll on my own health. In 1989 I left for a nine month stay as a worker at a monastery on the Big Sur coast to isolate and retreat from the AIDS world and enact my emotional healing in the sunshine and fresh air near the ocean. My time volunteering lasted for approximately two and a half years.” Harry’s work for the community has never stopped, though. For instance, as one of the co-authors of The San Francisco Principles, along with other activism, Harry remains engaged with the HIV community, particularly with long-term survivors of HIV/AIDS.

Another resolute volunteer since the earliest days of the pandemic is Cal Callahan. He recalls having volunteered in political, social, and environmental justice activities since the time he was sixteen years old. “It was a large part of my life,” he told me. “When so many friends began dying of HIV, I had to do something. I began volunteering with SFAF in 1985 when so many of friends had fallen ill or had already passed. I was assisting some of them in a caretaker capacity and was not able to take on more direct care, so I began filling requests for printed informational brochures and working in the Food Bank. A year or two later, I took the California AIDS Hotline training and began taking calls. I became a shift supervisor and was on the team that started the volunteer newsletter. I joined the staff of SFAF in 1995.

“As the epidemic calmed down, I stayed with it so other communities didn’t have to go through what my community did.” He has been involved in the Barechest Calendar fundraiser, Donna Sachet’s annual “Songs of the Season,” and many other volunteer activities.

It would be a cruel injustice to talk about volunteers in the fight against AIDS without mentioning Joanie Juster, an unstoppable straight ally par excellence. From 1988 through the present, Joanie has been a fierce, forceful ally and volunteer to the community. Just a short list of her involvement —

AIDS Walk: Joanie first volunteered to walk in 1988 as team leader for the SF Opera Team; she joined the AIDS Walk staff in 1994 and served as Teams Coordinator through 1996. She continued to volunteer, as team leader for the AIDS Emergency Fund team. She has been one of the top AIDS Walk fundraisers for fifteen years!

NAMES Project/AIDS Memorial Quilt: She started volunteering for the NAMES Project in 1988, sewing quilts and doing data entry; in 1989 she served as a Reader Coordinator at the Washington DC march and quilt display, a role she continues to play when the Quilt is displayed.

AIDS Emergency Fund: “I can’t remember when I started volunteering; some time in the early 1990s, collecting penny jars and processing pennies. Joined the Board of Directors in 1996, then was briefly hired as their first Development Director. Went back to volunteering; re-joined the staff in 2007-2010. Resumed volunteering, as well as heading their AIDS Walk team.”

Shanti Project: Joanie served as an emotional support volunteer from 1990 through 1992; she also facilitated trainings and was the team leader for Shanti’s volunteer support group for a few years.

National AIDS Memorial Grove: She has volunteered at the Grove since 2010, helping to coordinate events at the Grove, like the reading of names on the AIDS Quilt on Long-term HIV Survivors Awareness Day last year.

And all of that is a short, truncated list of the capacities in which Joanie has volunteered. And as it was for most volunteers in the early days, for Joanie volunteering felt like an obligation. When I asked her why she started volunteering, she replied, “ Oh, Hank, this is the big one. No way to tell this briefly, unless I simply say, Because my friends were dying, and at some point standing on the sidelines was no longer an option.”

She recalled the early days of the pandemic and what drove her to volunteer activism. “We started hearing rumors about a deadly new disease among gay men in 1981, 1982. By 1983 I heard that the first of my friends was infected. I was working in theatre and cabaret; I worked with many gay men. Fear was spreading. Every bar, every club, every theatre was holding AIDS fundraisers. People started disappearing… If you didn’t see an acquaintance for a month or two, you assumed they were dead. I read the AIDS Week column in the San Francisco Chronicle, and watched with horror as the Bay Area Reporter started printing more, and more, and more obituaries each week.

“By 1986 the crisis hit home: A phone call telling me that my good friend David had collapsed in Houston during tech rehearsal. He died in the hospital three days later. No one knew he had AIDS. I don’t even have a photo of him.

“In 1987 my close friend DW called one night. Hi, Hot Stuff. I’ve got some news. I have…pneumonia. Of course, we both knew what he meant, without saying it out loud. That was code for I have pneumocystis pneumonia, which means I have AIDS, which means I’m going to die. He told me he was moving back to Green, Kansas, to live out the rest of his life with his family. I was furious. Everyone I knew who had gone home to visit their families never came back. They all died.

“I still wasn’t ready to volunteer. I spent 1987 caring for my mother in her final illness. Then my Aunt Shirley. We lost Uncle John. Then DW died: All within six months. I was an absolute wreck, drowning in grief. I got a call at work about another death, and shed some tears. A co-worker timidly peeked over the wall of my cubicle and said, You get a lot of those kinds of calls, don’t you?”

Finally, a friend — Sharon Walton, a Shanti emotional support volunteer — referred her to Shanti as a client. “I thought only people with AIDS or cancer could get a Shanti volunteer. Didn’t matter: Sharon recommended that they take me on as a client, and next thing I knew, a charmingly down-to-earth former nun named Margaret called me up and suggested we meet. Finally, there was someone I could talk to about the grief I was carrying inside me. And after a few sessions, Margaret said, “You know, the best way to move beyond your grief is to help others.”

She created a Quilt panel for her friend David, the lighting technician who had died in Houston, and delivered it to the Quilt’s headquarters on Market Street in the Castro. “I looked at the nice, weary staff and volunteers who had let me in and realized I couldn’t just hand them more work. I had to stay and help. So I stayed, night after night, long past midnight, running to the Names Project after a full day of work at the Opera. I sewed panels together into blocks. I did data entry, entering the information from each panel into our database.” Thus started her association with the Quilt, which continues to this day.

“People sometimes ask why I keep volunteering for AIDS,” she told me. “And at this point, I simply don’t know how to stop. People with HIV and AIDS still need our help. I can’t walk away from them at this point. This work is my life, and my legacy.”

By selecting these four volunteer activists — Ed, Harry, Cal, and Joanie — from among the thousands of people who joined the fight against AIDS, runs the risk of short-changing other volunteers who charged to the front of the battle lines. So I asked each of them to name others deserving of mention here. Harry mentioned Steve Ibarra, Michael Hampton, Matt Sharp, and Bruce Ward, with a special shout-out to Jim Geary who led the Shanti training sessions. Cal asked for kudos for Jonathan Pon, who was very active in the cycling community and was a founder of Positive Pedalers group that rides in the annual AIDS Life/Cycle. Along with Stan Wong (volunteer with AIDS Walk, the Quilt, AEF, PRC, and the Grove); Neil Figuerelli (Board Member of AEF, created the annual Christmas Eve Dinner for PWAs), Kelly Rivera Hart (another non-stop volunteer activist), Mike Smith (co-founder of the Quilt, Executive Director of AEF), Joanie pinpointed “my personal hero, Leslie Ewing. She was one of the original crew at the NAMES Project. She and her partner Rebecca LePere coordinated volunteers, were on the organizing committee for the 1993 March on Washington, got arrested at a die-in at the NIH. She was president of the board of AEF (she’s the one who recruited me), and went on to a long career of activism in AIDS, marriage equality, lesbian rights, mental health services for LGBTQ…the list goes on and on. She is an icon in the community.”

Ed Wolf gave me a more expansive response: “The list is SOOO long… definitely someone from Open Hand, the AIDS Emergency Fund, the Godfathers, The Imperial Court System, The AIDS Health Project, PAWS, the Family Link, Kairos House and so on. Unfortunately, so many of them died and I wouldn’t know how to contact those who survived.”

I also asked each of these four to comment on the current status of volunteer activism. “As agencies merged and incorporated other diseases and conditions into their mission,” Cal Callahan said, “the work has largely moved to paid staff. Volunteers are still important to make fundraising events possible.” Ed Wolf amplified that summation. “My understanding is that the continued success of ARVs and PrEP have changed the role of volunteerism, at least in the US. We used to use volunteers from everything to providing emotional and practical support to HIV test counseling. Many of those roles are no longer filled by volunteers. An important role for volunteers these days is enrolling in clinical trials where HIV treatments and vaccines are being studied.”

“I am always curious why young people become involved with AIDS activism,” Joanie said. “My generation got involved because we HAD to – our friends were all dying. But younger generations didn’t experience that profound loss. I always ask young volunteers when I meet them. Many have holes in their family trees – uncles who died during the ‘80s who they never got to meet, people whose family histories have been shaped by AIDS.

“AIDS isn’t over,” she continued. “This has been my mantra for many years, as I work to raise money and awareness. We all know from experience that the squeaky wheel gets the funding, so it is up to us to keep speaking out, to keep advocating, to keep marching, for those who need our help.”

Commemorating 40 years

Join us every month in 2022 as San Francisco AIDS Foundation marks 40 years of service to the community.

On this occasion, we take a look back and share our storied history of leadership in HIV prevention, education, advocacy, and care, and HIV history in San Francisco and the Bay Area since the beginning of the epidemic.

As we look back on our history, we approach the future with hope, and with a renewed sense of all that our passion and ingenuity can bring to enact positive change in our community. We will act in bold and brave ways to reach an end to the AIDS epidemic, and ensure that health justice is achieved for all of us living with or at risk for HIV.

After 40 years, we will not lose sight of our commitment to our community, and our vision for a brighter future.