HIV trends: ‘One-size-fits-all’ fails our communities

Every year, the San Francisco Department of Public Health publishes an HIV Epidemiology Annual Report, sharing in-depth data from the previous year on HIV diagnoses, mortality, linkage to care, and other HIV-related outcomes. SFDPH released the 2019 report in September 2020, acknowledging that COVID-19 “has added significant new challenges in managing the HIV epidemic due to reduced HIV testing and care utilization.”

Although we do not know how COVID-19-related disruptions are impacting our progress toward “getting to zero” yet, there are a few concerning themes emerging from last year’s data that may continue — or worsen — due to shelter-in-place.

But first, some good news

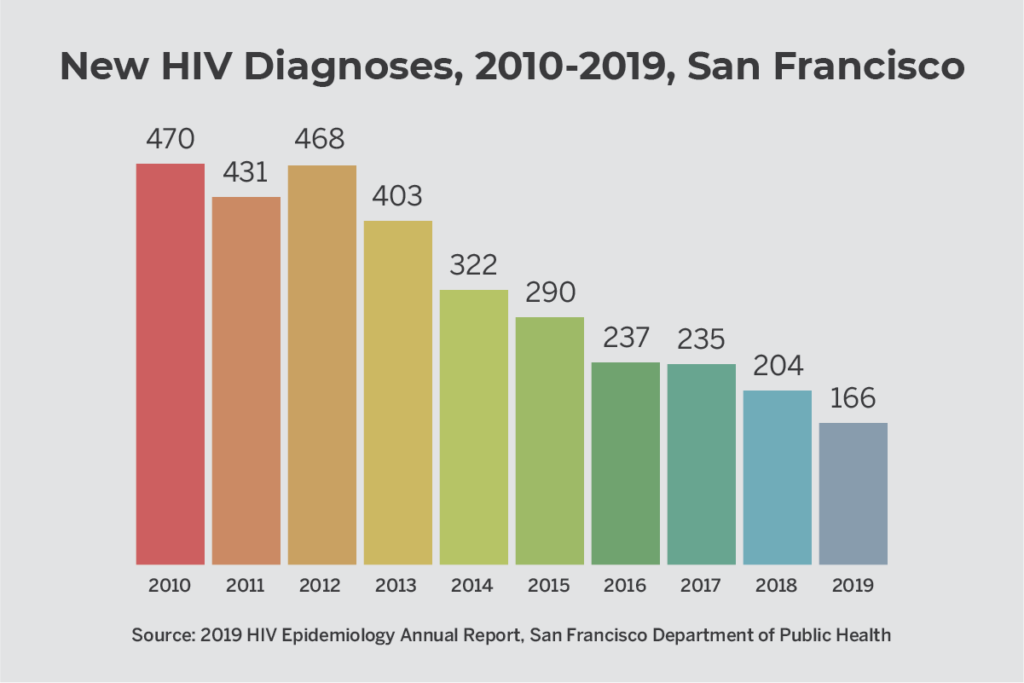

The number of HIV infections being diagnosed every year in San Francisco continues to decline: In 2019, there were a total of 166 new infections–a 48% decline from the number of infections five years previously in 2014. The rates of HIV diagnosis were stable or declined across all race/ethnic groups.

Viral suppression rates among people living with HIV are also high in San Francisco (74% of people living with HIV), compared to rates in California (67%) and the U.S. overall (65%).

PrEP coverage is very high in San Francisco, especially when compared to California and the U.S. as a whole. An estimated 71% of people with PrEP “indicators” (who may benefit from using PrEP) have been prescribed PrEP in San Francisco, compared to 22% in California and 18% in the U.S.

“There are a few things that have allowed San Francisco to reach many people with PrEP,” said Felipe Flores, associate director of PrEP and HIV positive services at San Francisco AIDS Foundation. “We’re in a state with expanded Medicaid, which means that more people have access to insurance than in states that have not expanded Medicaid. We also have a high concentration of PrEP providers. At Magnet [the sexual health clinic at SFAF], we have eight or nine people who can prescribe PrEP, which is more than some other counties in California have. Good access to public transportation in San Francisco and the Bay Area means that people can pretty easily get to clinics. And because San Francisco is a sanctuary city, I think that undocumented folks may feel more safe accessing PrEP services — which may not be the case in other parts of the country. We also have county-specific insurance coverage — Healthy San Francisco — for undocumented individuals, which helps people get access to services like PrEP.”

The Latinx community

As advances in PrEP, treatment as prevention and other HIV prevention methods change the landscape of HIV in San Francisco, the benefits to communities of color are uneven — with Black, Latinx and other communities of color disproportionately experiencing new infections.

As the number of white individuals diagnosed with HIV continues its steep decline year after year, Latinx and Black individuals make up a larger and larger share of the total new HIV diagnoses.

Over the past decade, the proportion of new HIV diagnoses happening among Latinx community members has been increasing. In 2010, 23% of new HIV diagnoses in San Francisco were experienced by Latinx people — in 2019, that proportion is now one-third (33%). About 20% of all people living with HIV in San Francisco and more than a third (38%) of young adults age 18 – 24 living with HIV in San Francisco identify as Latinx.

“It’s not a surprise that we’re not making as much progress with the Latinx community as we are in white communities,” said Jasmin Alvarez, director of clinical operations at San Francisco AIDS Foundation. “Unfortunately, racism continues to be a big reason why we continue to see health disparities. The current administration continues to spread the message that Latinx, Black, Brown, and queer communities don’t deserve equal rights, services, or health care in this country, which affects what care is available and even how willing these communities are to access the care they deserve. And there continue to be other health care access challenges for immigrants and monolingual Spanish speakers — everything from health care providers not having bilingual speakers available to HIV care and medications not being affordable to people without insurance. These are the things that we must — as a community and as a country — change.”

There has been progress in viral suppression for Latinx people diagnosed with HIV in the last year. After diagnosis, the vast majority (91%) of Latinx people are getting into HIV quickly — within a month — and most (84%) become virally suppressed within a year. Among Latinx community members diagnosed from 2014 to 2018, 44% started antiretroviral therapy (ART) within 7 days of diagnosis — a higher percentage than the average of 34% for individuals of all races.

African Americans and Black community members

Although new HIV diagnoses among Black and African American San Franciscans have been declining since 2010, HIV continues to disproportionately affect Black residents. Although 5.6% of San Franciscans identify as Black or African American, 17% of new HIV diagnoses were among people who identify as Black. And, Black and African Americans living with HIV in San Francisco were slightly less likely to be virally suppressed (70%) than white residents (77%) and all people in San Francisco living with HIV (75%).

“It is absolutely important for HIV organizations to not only do a better job of reaching Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) communities, but to really do the work to ensure that their approaches are less racist and that a racial justice framework is incorporated into everything they do,” said Flores. One problem with our health care system is that there’s been this ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach — even though we know that the way we connect with clients must be different for different communities.”

There has been progress on time to viral suppression for Black folks living with HIV in San Francisco. In 2017, Black and African Americans had the highest time to reach viral suppression (103 days) compared to people of other races (which had a median days to viral suppression less than 80 days). This has decreased by more than half — to 47 days — which is on par with the level for whites (52 days) and Latinx people (43 days).

People experiencing homelessness

About 8% (717 people) of people living with HIV in San Francisco (with housing status information available) were experiencing homelessness or were living in a single-room occupancy (SRO) facility during 2019. Of those individuals, 9% identified as trans women, 17% as people who inject drugs, and 30% were men who have sex with men who inject drugs. A substantial proportion were people of color: about a quarter (24%) were Black or African American, and 22% were Latinx.

In recent years, the percentage of people newly diagnosed with HIV who are experiencing homelessness has been increasing. In 2019, 18% of people newly diagnosed with HIV (30 people) reported being homeless.

Treatment outcomes are particularly startling for people without housing — with viral suppression rates falling far below those for people with stable housing. Only 68% of people newly diagnosed with HIV in 2018 were virally suppressed in 2019, compared to 85% of people with housing. And among all people living with HIV who reported not having stable housing, only 39% were virally suppressed compared to 76% of people with housing.

“We know that there are so many challenges that people who don’t have housing face when it comes to accessing HIV prevention and treatment,” said Alvarez. “It’s so important for health care providers to make sure that we really understand and can accommodate those needs — whether it’s support from a case manager or social worker, mental health care, or access to medications and care no matter what their financial situation is. We’ve seen people who get a diagnosis, and are kind of left to figure it out, but we have to build in systems of care that allow people to get the care that will work for them.”

Trans individuals

Although the numbers are small, the proportion of new diagnoses among trans men and trans women increased from 2018 to 2019, from less than 1% to 1% among trans men, and from 3% to 7% among trans women.

More information is available about trans women than trans men, since the absolute number of trans men included in the report is so low.

Out of the 106 trans women newly diagnosed with HIV from 2010 to 2019, most were women of color: 40% identified as Latinx, and 26% were Black or African American. 30% reported using injection drugs. Among all 418 trans women living with HIV, more than three-quarters were women of color: 36% identified as Latinx, 31% were Black, and 9% were Asian or Pacific Islander.

People who inject drugs

In 2019, 17% of new HIV infections were among people who inject drugs (7% among people who inject drugs; 10% among men who have sex with men who also inject drugs). This represents a slight decline from the previous two years, where about a quarter (24%) of new infections were among people who inject drugs.

People who inject drugs had lower rates of viral suppression: Among all people living with HIV who inject drugs, 66% of people who inject drugs and 69% of men who have sex with men who inject drugs were virally suppressed (at the most recent viral load test in 2019), compared to 75% of people overall.

“Unfortunately, people who inject drugs are well-experienced in the kind of stigma from health care systems that can prevent people from getting the HIV care they need,” said Laura Thomas, director of harm reduction policy at San Francisco AIDS Foundation. “People who use drugs — who may also be experiencing homelessness — may find that health care providers assume they are drug-seeking or just don’t take their health care concerns seriously. So they end up showing up at syringe access sites for their health care needs, and nowhere else. That’s why it’s so important for us to be able to provide access to HIV testing, prevention, and linkage to care in those settings.”

For people living with HIV, drug overdose continues to be one of the leading causes of death. From 2015 to 2018, a total of 121 San Franciscans living with HIV died from a drug overdose.

“Overdose deaths are becoming a higher and higher proportion of deaths among people living with HIV, and I think this is something that is only going to get worse — especially this year because of COVID-19 and shelter-in-place,” said Thomas. “In general, overdose deaths have been increasing in San Francisco because fentanyl has arrived. And this overlap between overdose and the HIV community is one reason overdose prevention is an issue for San Francisco AIDS Foundation, driving our advocacy around supervised consumption services.”

Impact of Shelter-in-Place and COVID-19

We do not yet know the full extent of how COVID-19 and shelter-in-place mandates have impacted HIV transmission, linkage to care, viral suppression rates and other HIV outcomes in San Francisco, although experts say that hard-won progress is “at-risk”.

In July, San Francisco’s Getting to Zero Coalition shared that viral suppression rates may have decreased by 33%, health facility HIV testing has decreased 40%, and PrEP visits have been “spaced out.”

“Getting to Zero recognizes that COVID-19 poses a serious threat to the health and livelihood of persons living with HIV and for those at risk for HIV. Moreover, with reductions in HIV testing, it will be difficult to assess trends in new HIV diagnoses over this calendar year,” the statement read.