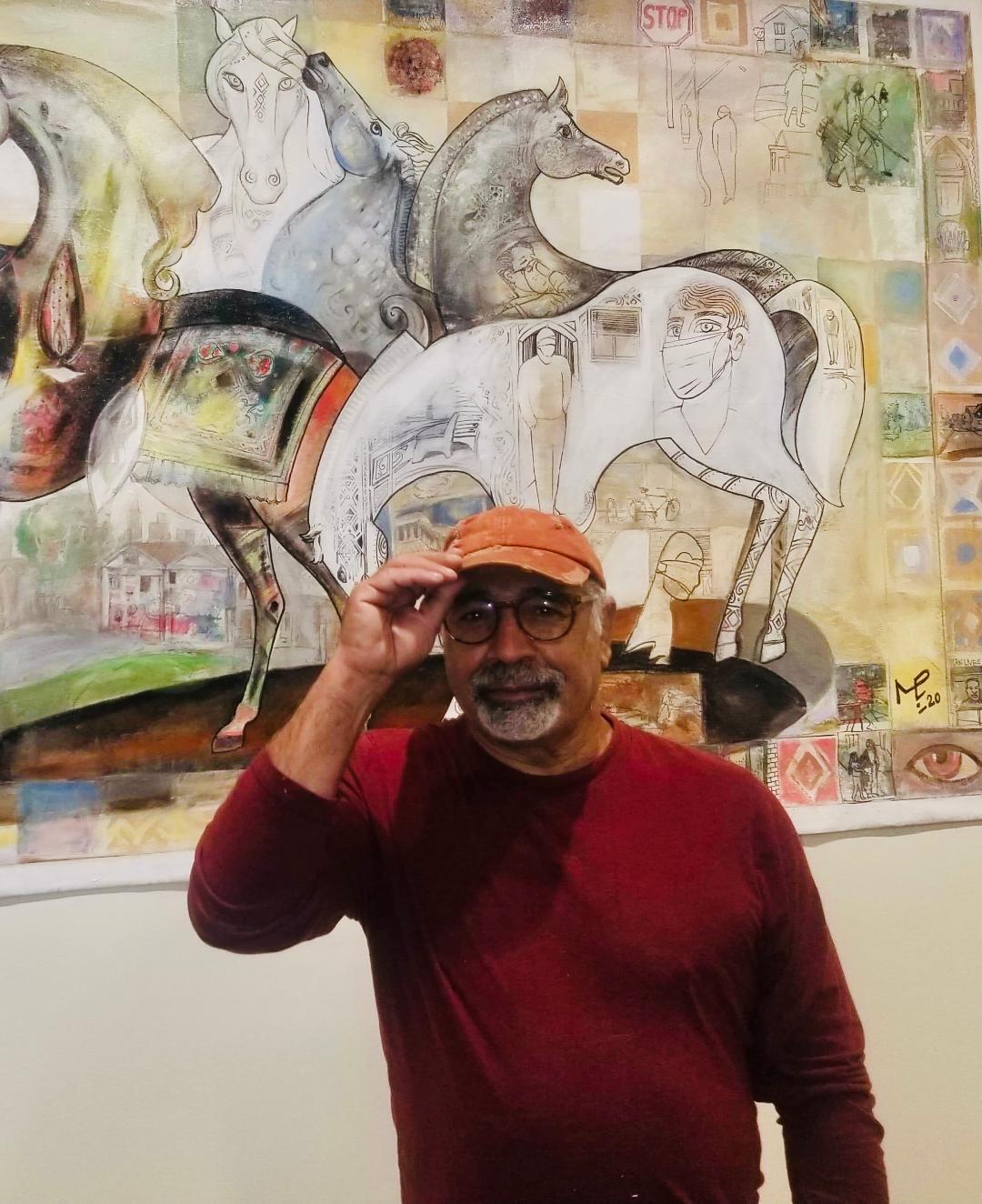

A chat with artist Mokhtar Paki: “Beasts are interesting, beautiful, and even sexy”

On display at the gallery of the health and wellness center Strut, in the Castro, is art by Mokhtar Paki, a visual artist and gay man originally from Iran. Paki’s art explores queer homoerotic Iranian icons such as Varun, the ancient god of homosexuality, and other “beasts” which Paki says he finds “interesting, beautiful, even sexy.”

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Paki’s art has been on display for about eight months (artists featured at Strut usually have art on display for one month at a time). In this article, we introduce to the community Paki’s art, the themes his art explores, and how his art has survived the pandemic.

RAY: Hi Mokhtar, nice to meet you. We’re keen to learn about your art and influence.

In your words you say: “I’m an active member of the society I live in now, and I don’t want to be boxed in the words like “Diaspora”, “Identity”, “and Refugee”. My works as an artist could be good enough to represent me.” You don’t want to be boxed?

MOKHTAR: In one of my painting exhibitions of 2007, I had a mixed media work called “Katrina,” a face of a black child and a devastated landscape of the 2005 hurricane in New Orleans. A journalist at the show looked at the painting and asked me: “Why did you paint this?” I was puzzled by the question and stayed silent. He continued: “This is an American disaster. You are from Iran.” He then smoothed his tone by saying: “There are unfortunately a lot of disasters going on there. Say, ‘Abu Ghraib.’” He’d obviously mistaken Iran with Iraq.

He, like many people in the US, expected me to avoid doing a certain art. That expectation usually comes hand in hand with an encouragement that tells me what type of art I should do.

I’m an Iranian American, a political refugee and proud of my cultural identity. But I’m above all a human, and an internationalist. In countries like the United States, the artists who are the members of the minority groups are usually encouraged to do their art projects focusing on identity, heritage or their political or social problems. They’re turned into useful, tamed, and harmless civilians who help the grant–giver.

I understand why Miles Davis became angry at an interviewer who asked him “Why don’t you have a concert for Africa in Africa?”

RAY: “Beautiful Beasts” – Why did you choose this name?

MOKHTAR: Perhaps because I never thought that being a beast means ugly. The words like “beautiful”, “ugly” or “beast or beastie” are relative terms depend on who use them. A lion, is a strong beautiful animal, yet we call it a beast. When I was a child, I loved the fairytales and mythological stories told by my mother or recited by my cousin from the Iranian epic book “Shahnameh”. I was more interested in the villainess creatures of those tales. One of them was a deev called Akvan, a monster with horns and tail and spotted body. He wore skirt and tattoos and pierced his nose and nipples. He never wore underwear, and you could see his private parts. His tongue was out and their eyes were wide open even when he was killed. And he was usually killed, because he was a villain. Later in my life I studied about these deevs and found out that they used to be the gods before monotheism. The religious institutions of monotheist Zoroastrianism, demonized them and pictured them in unflattering look. I found their images interesting, beautiful and even sexy.

RAY: In Beautiful Beasts art, you depict Varun, a homosexual god that was banished with other deities by a powerful Monotheism of Zoroastrianism about 1000BC in Iran. Looking at America today, and Iran today, do you see the mistreatment of Varun as similar to the way homosexuals are treated in America and Iran today?

MOKHTAR: The banishment of Varun by Zoroastrians symbolizes the homophobia that followed. The goddesses received the same treatments in most monotheist religions, and that also symbolizes the sexism by patriarch societies.

RAY: The namesake of Varun the homosexual is still the god of the sea in India today. That means the god of the sea is potentially a friend for Varun. Do the queer folks find friends easily in America in 2021 beyond their community?

MOKHTAR: Queer folks have an easier time in 2021 finding friends in the community beyond their own. But, nothing is certain and shouldn’t be taken for granted. The recently passed Texas law on abortion is an alarming sign of the fragility of a liberal achievements.

RAY: The name “Beautiful Beasts” here is related to the “deevs” (some homosexual-acting gods before monotheism). Does it mean that queer folk once held power in Iran?

MOKHTAR: In Iran, like in any society with polytheism, there were gods and followers who were not scared of sexual acts or certain moral codes. In ancient India as well as pre-Christian Greece and Rome, sexuality and homosexuality was more tolerated. It doesn’t mean homosexuals held power, although their powerful leaders were guys like Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, both homosexual. There had been widespread acceptance of same-sex relationships, including stories of heroes like Hercules and Achilles, as well as poetry from Sappho and philosophy from Plato.

But three thousand years of monotheism in Iran and beyond has done effective damage to eliminate the rights of queers and women.

RAY: In one of your drawings, a woman-looking-figure is squeezed between thorns/wires yet the person is naked and wants to be free. How has the COVID pandemic squeezed the queer community?

MOKHTAR: I studied architecture and my recitation is about “reconstruction following the disasters.” Pandemics, like all other disasters, exacerbate inequality. People of color, women, minorities and of course LGBTQ communities were affected immediately. This was just like a sequel to the AIDS epidemic for some folks.

RAY: Now the exhibition. COVID-19 means your exhibition was restricted: virtual and limited numbers. What did you lose compared to say years like 2019, 2018…?

MOKHTAR: I learned a lot during the pandemic show. But what I lost was mostly the audience. I was hoping the show could be shared with a wider audience and in-person.

RAY: Let´s assume COVID is with us for the next 5 years; is it sustainable for an artist like you to only do virtual exhibitions/limited person exhibitions for the next 5 years?

MOKHTAR: I’m not sure. We should find a way to share our works and world with people directly. But one thing is sure: I never stop working.

RAY: You have lived in America for 34 years as an artist. If you were living in Tehran, Iran today, would your art be permitted?

MOKHTAR: Tehran has a huge art scene and a blossoming one. I’m sure some homoerotic arts will be banned in Iran, but Iranian homosexual artists have found a way to do their work. There are examples of the main Iranian classic poets, Hafez (14th Century), Saadi (13th Century) and Rumi (13th century).

I personally published my epic novel “Shamayel Mana” -“Icon of Mana” in Iran about fifteen years ago. The title character of that novel is a bisexual man.

To learn more about the artist, visit mokhtarpaki.com.